How do antiquities return to Egypt?

October 24, 2009

On the 7th of October 2009, the French Culture minister announced the Musée du Louvre would return to the Egyptian authorities five fresco fragments supposedly stolen from a tomb in the Kings’ Valley (Louxor). Why did it break the news?

The issue is not really new. Since the early 2000’s, the problem of cultural property have gained visibility and became a source of diplomatic and political conflict. Two opposite positions are confronting. On one hand, institutions in archaeological-source countries claim for the right to be returned, rapatriated or restituted “their” “looted” artifacts as part of the national heritage. On the other hand, 18 museums from antiquities-importing countries have signed the Declaration of the importance and Value of Universal Museums (2002) stating the artifacts in their collections do not belong to a nation in particular but to the entire Humanity. As both arguments can be considered as valid, it results in a deadlock situation such as in the case of the Parthenon/Elgin Marble whose property is claimed at the same time by Greek authorities and the British Museum.

The issue is not really new. Since the early 2000’s, the problem of cultural property have gained visibility and became a source of diplomatic and political conflict. Two opposite positions are confronting. On one hand, institutions in archaeological-source countries claim for the right to be returned, rapatriated or restituted “their” “looted” artifacts as part of the national heritage. On the other hand, 18 museums from antiquities-importing countries have signed the Declaration of the importance and Value of Universal Museums (2002) stating the artifacts in their collections do not belong to a nation in particular but to the entire Humanity. As both arguments can be considered as valid, it results in a deadlock situation such as in the case of the Parthenon/Elgin Marble whose property is claimed at the same time by Greek authorities and the British Museum.

The new thing about this recent return is that the Louvre is one of the museums that signed the 2002 Declaration. For the first time, one of those museums agrees in such a short time (less than two weeks) to return the claimed pieces… without negociating any condition. How was it possible?

In my opinion (and without taking any judgement on the validity of the arguments), this return can be considered as the succesful result of the heritage policies initiated by the Egyptian authorities since 2002. These policies relate the struggle against illicit art and antiquities traffic, the return of stolen or looted artifacts, the management of archaeological fieldworks and the question of funding egyptian authorities, all this in a media perspective. The figure of Zahi Hawass, the so-called Lord of Egyptian Antiquities, overshadows all the debates in a nationalistic rhetoric to claim the Rosetta stone, the Nefertiti bust as well as minor objects (see this interesting sum up).

The following short text summerises the mechanisms of these policies as proposed to a 2008 conference at the European University in Firenze “Illicit Traffic of Cultural Heritage in the Mediterranean Region“ organised by Ana Filipa Vrdoljak and Francesco Francioni. I am currently developing these arguments in my PhD thesis.

Bargaining Processes Versus Illicit Trade: An Egyptian Case-study.

This article analyses the current policy concerning illicit trade of artefacts in the Egyptian context. Since 2002, the control of illicit trade became a priority of the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA, body in charge of the Egyptian Heritage). This policy includes: restitution of Egyptian artefacts illegally exported, now being exhibited in international museums or being sold on the art market, and protection of endangered artefacts still within the country.

This policy is supported by three negotiation mechanisms: diplomatic, legal and “bargaining”. The two first mechanisms are formally supported by international conventions but they are long and expensive. In Egypt, the third mechanism became the modus operandi. It consists on a bargaining process with the international archaeological teams and museums:

- Diplomatic mechanism: The SCA is now limiting the access to archaeological researches; the fieldwork missions are just allowed if the respective museums engage the restitution of required antiquities.

- Legal mechanism: To protect artefacts from illicit trade related with internal corruption, the SCA then requires the international teams to remunerate the SCA inspectors.

- “Bargaining” mechanism: As a result, it raises the cost of loaning national collections for international exhibitions. These additional funds are being used by the SCA for the improvement of inventory and conservation measures.

My contribution aims to put in evidence the use of alternative mechanisms which are not regulated by international conventions. It consists on practices based on bargaining processes between national authorities and international archaeological teams in order to raise funds to support local policies aiming to prevent illicit trade [as well as the return of antiquities from international museums and providing financial support to the SCA].

Related posts on this blog (in French):

On Zahi Hawass‘ sense of maneuver

On cultural property in a historical perspective

On restitutions and heritage-making

picture:

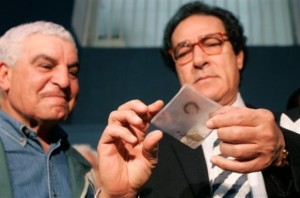

- Egypt’s antiquities chief Zahi Hawass, left, and Culture Minister Farouk Hosni, right, examine a 3,200-year-old sample of hair from the pharaoh Ramses II during its unveiling at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Egypt Tuesday, April 10, 2007. The samples of hair, linen bandages and resin used in the mummification were returned to Egypt after disappearing 30 years ago in France and discovered after being put up for sale on ebay November 2006 by a French postman. (AP Photo/Ben Curtis)

[…] sujet: – un portrait de Zahi Hawass – une mise en perspective des questions de propriété – Une ébauche d’étude des mécanismes institutionnels de restitution – Whose Pharaohs? Posted by […]